One of the things I love about living in the beautiful hills of Dundee, is the many talented, passionate, creative people who live here as well. Our next door neighbor Bryan, just put in a vineyard, a mini golf course, and a zipline, Lanette makes beautiful art, Dennis makes furniture out of reclaimed barnwood and wine barrels, and just down the road and around the corner live John and Jeremi, the talented duo behind Pollinate Flowers. They are also big proponents of permaculture, creating on their farm a beautiful, healthy food forest. I knew a little bit about companion planting, and permaculture from previous reading and experiences, but I had never heard of a food forest before -- until I saw their posts on social media. I was first drawn to Pollinate Flowers because of their beautiful Instagram pictures, but what really hooked me were the insights and wisdom that went along with the pictures: both the lessons they shared and the love that went into their project were captivating. And because I not only want to learn more about permaculture and food forests, but also want to meet more of my talented neighbors, I sent them a message, asking if I might barge in on them sometime to see their work. Thankfully they said yes, so on a cloudy and cool fall Monday morning in November, I headed down the street to meet them and see what they were up to. It turns out they are up to quite a lot, actually. In the time that they have lived there, John and Jeremi have transformed a manicured, park-like, grass field into a beautifully diverse compilation of both flowers and rowed plantings of lettuce, fennel, broccoli, collards,etc, surrounded by meandering paths lined with lime balm, thyme, redwood sorrel, dahlias, love-in-a-mist, ginkgo, hawthorn, and many many other trees, perennials, flowers, shrubs, and herbs. A food forest, full of life and diversity. There are also bat boxes and bird boxes scattered about, a beautiful, tall arbor that supports grapes, a fire pit, and tucked away places to sit and contemplate. And as we walked and talked, we also sampled many of the gifts of the land. I ate my first Dahlia (it tastes like carrots), nibbled on a cornflower, and inhaled the sweet scent of lime balm. I was in heaven. But it wasn’t all chatting and eating flowers -- there were lessons to be learned. And here are a few: 1. What exactly is a food forest? Just as in a natural forest, a food forest is the idea of multi-layers: growing multiple species of plants of varying sizes and root systems with varying needs that make varying contributions to the system. It’s about companion planting and diversity and creating a healthy balance in the soil so that plants help each other, attract beneficials, and create places for insects, birds, and other critters to thrive. When this happens and the ecosystem is in balance, insect pests won’t take hold and the soil will replenish with each cycle, so there is no need for pesticides and only a minimal need for soil amendment. John compared this to our own personal ecosystems: good, nutrient-rich soil for plants is the same as good, nutrient-rich foods for us -- both help to grow healthy living things. If the soil is healthy, the plant will be healthy. 2. There’s a whole lot going on under our feet. As John and Jeremi explained it, there are millions of little organisms working together below the ground to support everything we see above the ground. Jeremi compared it to the New York City subway system. All that great stuff we see above the ground wouldn’t exist without the underground infrastructure that keeps everything moving. So it’s just as important to care for everything below the ground as everything above the ground. One of which is the fungi we don’t see. 3. Fungal networks are crucial: You know that white stringy looking fungus you dig up every so often out in the garden? Well, it’s actually a vital part of that underground system. It’s a hollow fungus called mycelium that is a part of something called a Mycorrhizal network (also sometimes called the Wood-Wide Web). A Scientific America article explains how the mycelium fungus “infiltrates the plants’ roots. But it does not attack — far from it. The plant makes and delivers food to the fungus; the fungus, in turn, dramatically increases the plant’s water and mineral absorptive powers via its vast network of filaments.” These fungal networks also aid in the decomposition process, break down toxins, and allow plants to share resources with each other. AND these networks allow older trees to share resources with younger trees until they are established. Amazing! The lesson here is that... 4. Tilling the ground hurts the soil: John explained how when we till or dig up an area of soil, it breaks the Mycorrhizal networks, interrupting not just nutrient supplies but also communication between plants. For example, one study showed how the network acts “as a conduit for signaling between plants, acting as an early warning system for herbivore attack.” John gave an example of how plants that had the network in tack were able to warn other plants of an aphid infestation, so the plants further down were able to “invoke herbivore defenses” to keep the aphids at bay. So when we break up the soil all of the plants in the area are weakened. 5. Let it lie: I was getting ready to do some clean up around here, but as we were talking, I realized how important it was to keep some spaces untouched until the spring, allowing for some of the beneficial insects to have places to go through their life cycle. Basically, the more ladybugs and other beneficials you can overwinter in your garden, the fewer infestations you will have down the road. That’s also why having perennials is so important. A plant that lives in the garden for years instead of months will offer a more consistent and safe place for those beneficial critters to live. 6. Enjoy the journey: As John and Jeremi talked about their journey, from a kid who took over his mom’s garden (John), to buying their property and transforming it into their beautiful farm, I was struck by the joy on their faces as they talked about how important each step has been and how they were still learning, experimenting and growing. This really resonated with me because as I was starting on our little lavender farm, I sometimes became impatient with how slow everything seemed to be moving. But these two were a great reminder to enjoy each step, learn from each day, and connect more deeply with the earth and with those around us. Thoreau once said: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation…” John and Jeremi are the reminder that we don’t have to live our lives that way -- that each of us has a song to be sung, which is often drowned out by the clamor and clanging of our world, but that if we are brave and listen and follow our hearts, we can sing a really beautiful song that touches everyone around us. They inspire me to continue to enjoy my journey, learning more every day about this big beautiful planet we live on -- and about the many miracles under our feet.

0 Comments

You know all of those sayings and quotes about dogs that you’ve read over the years? All of them are true. Yes all of them. Yes, dogs are our best friends. Yes, all dogs go to heaven. Etc...

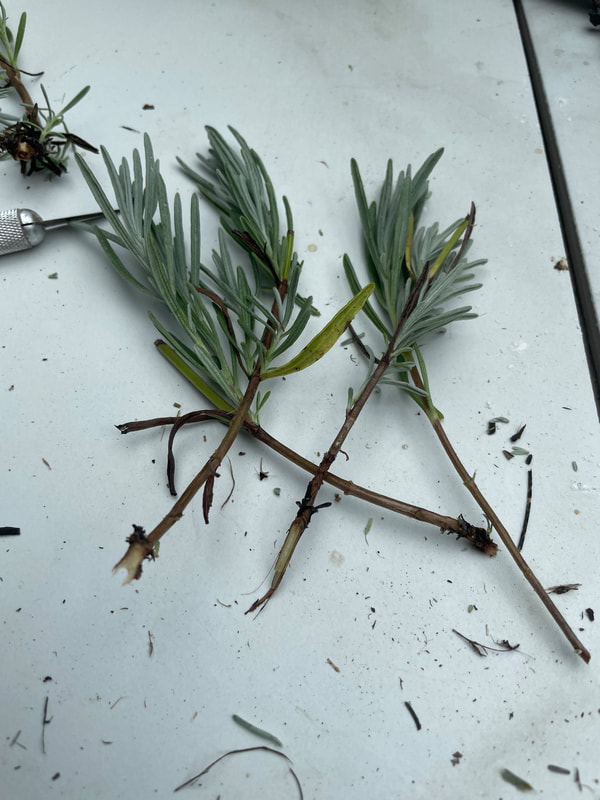

Case in point: Mornings start with Henry, our white Lab, politely barking (just one short bark) that it’s time to get up because he needs to get fed. I walk out to the living room where all three dogs sleep and they greet me with barks and wagging tails, but Henry throws in his “bucking bronco” dance, bouncing back and forth, tailing wagging, tongue hanging out, because he's THAT excited about food. After we’ve all had our breakfast, I open the back door and announce that it’s “time to feed the goats!” and Rammus just about pops a gasket with his high pitched and very loud barking, acting as if this is the very best part of his day, and then runs just a little ahead of me to clear the way, running back and forth between the goats and the chickens, giant dog smile on his face. Henry trots more slowly behind us, pausing somewhere between the house and the barn because he has found something to nibble on -- blackberries, grass, goat poop…anything really. Henry lives for food; Rammus lives for his “job.” Rosie, the newest member of the pack (and oh so sweet), harasses both of her older dog brothers equally, bounding back and forth between the two -- biting Henry's collar for a minute and then running off to steal a ball from Rammus. So. Much. Energy. As the day progresses, everywhere I go around the farm, they are right there by my side -- standing guard as I work in the field, walking right next to me as I am doing my chores, and laying right next to my feet when I’m reading or watching TV. Sometimes I talk to them about what’s on my mind, and they listen politely (and as if I have just said the most profound thing ever!), and sometimes we just hang out. And when the day is done and it’s time for bed, all I say is “OK pups, it’s time for sleeping,” and they get up and walk over to their beds. These three sweet puppies are my daily companions, protectors, confidantes, and comic relief. How is it even possible to have a bad day with such pure, loving souls by my side? I don’t know that we deserve them, but a big shout out to the Creator, for knowing we would need such steadfast companionship on our turbulent human journey.  Who doesn’t love free plants? Well, that’s exactly what propagating gets you. Most people think of planting seeds when it comes to propagation, but in the case of lavender it’s a little more complicated than that. First of all, some lavenders don’t produce seeds. Lavandula x intermedia is a hybrid species, and it does not produce seeds, so the only way to propagate this kind of lavender is through cuttings. Although angustifolias do produce seeds, those seeds can’t be counted on to produce the same qualities as the parent plant. Seeding is also a slower and less reliable method than propagating from cuttings. So all of the lavender farmers I know propagate using cuttings. It’s actually quite easy since lavender takes very well to propagating from cuttings and creates an identical plant to that of the parent plant. Propagation can be done in the Autumn (for Springtime planting) or in Spring (for planting in Autumn). I prefer the former because Springtime planting means that those baby plants don’t have to contend with winter weather as they are just starting out in the ground. Though I’ve also known farmers who swear by planting in the Fall so the baby plants don’t have to contend with summer heat. So I guess it comes down to personal preference. Propagating is actually a pretty easy process. Here’s how I do it: First I set up my seedling trays, filling the cells with a seeding mixture. Then I water the mixture well so that once I insert the cuttings, they are in a nice secure space with minimal jostling. Next, I find a nice healthy plant out in the field and cut off a few branches. Lavender can be propagated from either soft cuttings or woody cuttings. Soft cuttings come from that part of the plant where the stem is a little bit greener and softer. A woody cutting is just as it sounds -- the browner, stiffer part of the stem. Next, I bring the branches to my potting table and look for a 2-3 inch healthy looking side stem. I break it off of the branch and then strip the bottom 1 inch of leaves. Using an exacto knife, I then slice the bottom stem at an extreme angle so that it’s looking pretty pointy. Some farmers then dip the stem into rooting hormone and some do not. The rooting hormone helps prevent rot and promotes quicker root growth, but lavender does take well to propagation without root hormone. I usually use rooting hormone, just to get those roots off to a quick start. Once all of the stems have been planted, I water again and continue to water and mist every day for the next few months. I'm very lucky to have a greenhouse where I can keep the plants at a consistent 70-75) -- but if you don't, a heating mat will help the plant to take root.

Once I see roots just coming out of the bottom of the cell, I transplant the new plants to a slightly bigger pot. To do that, I gently pull the lavender seedling out of its cell and plant into a 3-4 inch pot filled with planting soil, watering well once I’m done. After a few weeks, the plants will start getting bushier. There are usually quite a few plants that get a little too enthusiastic and start sending up blooms. As painful as it is to do so, I snip those blooms off so that the plant’s energy is directed to its roots. Once the plant has started to fill out more and the roots have spread out in the pot, it’s time to plant into the field. I usually take the tray of plants out to a protected area of the field and let them get acclimatized before I transplant them. And there you have it! Free plants!  Summer evenings, after a day working in the field, one of my favorite things to do is to grab a glass of something delicious and sit out on our back shaded patio to distill lavender. The giant kiwi plant crawling up a very sturdy trellis gives me shade and the scent of lavender makes this not only a very relaxing activity, but a calming one as well. Distillation itself is a quite magical process. You put a bunch of plant material into a metal cylinder, place that on top of a giant pot of boiling water, and watch in wonder as water and oil come out of the attached metal tubes. Well I guess it’s a little more complicated than that...but not by much. Here’s the process in a little more detail:

The nifty oil separator I have has an opening on the bottom, so after the distillation, I just let the water out (which is hydrosol) and I’m left with a beautiful layer of oil that I then put into pint jars, ready to be used in soap, salve and all kinds of other great lavender-y things. I’ve also started distilling some of the other plants we grow on the farm, like Rose Geranium and Rosemary, since I use these oils in several of our products. Interestingly, I don’t get nearly as much oil from these plants as from the lavender, but I’m grateful for any amount I get. And it just gives me an excuse to plant more of each. It all seems so simple now, but I’ll never forget our first attempts at distillation. Essential oil distillers can be a bit pricey -- even a small tabletop distiller runs several hundred dollars, so when we first decided to give distilling a try, my engineer husband said “How hard could it be?” watched a few youtube videos and pieced together our own distillation contraption taking some of his beer brewing equipment, adding a modified pressure cooker, a few plastic tubs, a pasta strainer and some copper tubing. That should work, right?

Well, it did and it didn’t. We got some lovely hydrosol, but not much in the way of essential oils. I think with some tweaking we might have gotten it to work, but even from just the hydrosol we were able to get, I was hooked. And my birthday was coming up. So a shiny new stainless steel distiller was my birthday present that year and I was thrilled. Now all I have to do is attach a few hoses, start the propane burner, shove a bunch of lavender into the top container, grab a glass of wine, and inhale the sweet aroma of lavender as it distills. I’m pretty sure our neighbors are relaxing about as much as I am as the scent wafts through the trees and down the road. Alchemy at its finest, I’d say. Last year, we decided to try our hand at beekeeping. We thought we'd start with two hives, so we went to a beekeeping class, bought all of the supplies and then, of course, purchased a nuc of bees. But soon after last Fall's fires, we realized one of our hives had swarmed. And then a month after that, the other one disappeared as well. There was no sign of them.

So over the winter, we started the process of cleaning out the hive boxes, questioning whether we would continue our beekeeping adventure. And then in April, before we had cleaned out the second box, we caught a swarm of bees. Well “caught” isn’t the right word actually. They just moved in. So our beekeeping adventures were destined to continue. We realized, however, that as busy as our lives were at the moment, we needed help to get going again. Enter Matt the beekeeper at Oregon Beekeeper. He will be managing our hives and teaching me at the same time so that I can take over the beekeeping duties eventually (after harvest). Thank goodness for Matt! However, this isn’t the first time we’ve had help with our beekeeping aspirations. Back in San Diego, we were lucky enough to be part of the “host-a-hive” program that Hilary Kearney (The Girl Next Door Honey) had implemented. It was a great introduction to beekeeping -- I was able to provide a safe space for a few colonies and observe and learn, but I wasn't responsible for the care of the hives. But we did get off to a quite exciting start! On the evening of the bees arrival, Hilary drove up in her white Prius, filled with bee supplies and two bee hives, and the first thing she said as she walked up was…”we have a bit of a problem.” Not the first thing I’d necessarily want to hear from the bee expert, but OK. Apparently she’d had what she called a “bee leak.” Bees had escaped and had clumped onto the side of their hive. In her car. While she was driving. On the freeway. She had driven almost an hour to get to our house with two leaky hives in her back seat! This woman was made of steel.... The problem at this point was -- how would we transport a leaky hive down the hill to their designated spot without getting stung too many times. Hilary had her bee suit of course, but the hive was really heavy and she had been counting on our help. So we came up with a plan -- if we could just get the hive out of the car and over to our wheelbarrow, we could slowly wheel it down the hill. And by “we” I mean Hilary and Mark. He volunteered to hold the other end, with a sturdy pair of gloves and a desire (perhaps?) to make up for all of the times he had harassed bees as a kid. I stepped into the background, to stay out of their way, and “supervise” as they carefully pulled the hive out of the Prius. A couple of bees broke off of the clump and started swarming around the garage light with an angry buzzing. After a few careful steps over to the wheelbarrow and a gentle landing, Hilary and Mark headed down the hill with me and a flashlight leading the way. Hive number one was put in place with no incident and we headed back up the hill to retrieve hive number two. Hive number two was retrieved from the Prius, gently placed in the wheelbarrow, taken down the hill, put in place and we were all set. Hilary then got a bottle of oil from her car to put in the bowl-like footers of the hive to keep ants away from the honey and we discussed how to get an accessible water source for the bees so that they didn’t feel compelled to raid our neighbors’ bird baths or fountains. Suddenly I heard a very angry buzzing near my ear and Hilary calmly said “You’ve got a bee in your hair -- come here and let me find it so it doesn’t sting you.” Now granted, one of the questions Hilary asks before she places a hive is ”How do you feel about bee stings” and I answered “I have no problem with them.” But the last time I had been stung was in high school, on my foot, when I had stepped on one. I had never had an angry bee trapped in my hair before. So although I was desperately wanting to jump around and/or start running, I didn’t. Because well, “nerves-of-steel” Hilary was there and I didn’t want her to regret her decision to place a hive with us. It took great self-control for me to stand there and let her look for the bee in my hair as I heard it getting angrier and angrier. Then came the sting. The little gal had fallen into my shirt and landed at the top of my chest and so that’s where she stung. And THAT was when I started dancing around a little trying to flick her off. No nerves of steel for me. I was a bee wimp. There was no stinger so it didn’t hurt too badly, but I went inside to take a look, try to regain my composure, and put a saliva/baking soda mix on the sting, as Hilary had suggested. However, once inside, I could still hear the angry buzzing! So now I really started freaking out. I ran through the house thinking it was following me, I flipped my hair around, I twirled around and ran through the house some more -- but the buzzing was still there. Hoping desperately that 1) I could get away from the bee and 2) that Hilary wouldn’t see me through the window, I continued to twirl, and run and flip my hair. But that sound followed me everywhere. Finally, Mark came in, saw me running around, made me stop, found the bee hanging onto my pants, and put it out of its (and my) misery. And at that very moment, Hilary came in with a big jar of honey. My initiation was complete -- 1 bee sting and 1 jar of honey. I was officially a member of the beekeeping community. Hopefully this new adventure in beekeeping won't be quite as exciting!  Summer on a lavender farm is every bit as wonderful as you would imagine -- but very short. Since lavender only has one big bloom per year, lavender growing season is really only about 6 weeks -- maybe a little longer if you’re lucky and get a nice “bonus bloom.” So it’s a very busy time -- and goes by in the blink of an eye! Let me see if I can paint a picture for you… In the summer, the sun comes up here in Northern Oregon around 5:30. I’m not going to lie and say I’m out there working at 5:30,more like 7:00. After I’ve had my tea. And enjoyed a little bit of the morning. For the first part of the summer it’s really all just a waiting game, celebrating each step along the way. First the plants green up and that’s exciting and a little scary because at this point I can see how many plants have made it through winter. Next, the little heads of the lavender stems start peeking up through the leaves and push their way through, reaching for the sky. After a few weeks, the heads get a little bigger until finally, the first peak of purple comes through. Over the next few weeks, the field will get just a little more purple every day. But we aren’t there yet! The lavender isn’t ready to harvest until the stems get strong enough, right around the time that the first few flowers pop. Which is right when the bees show up! Now it’s time to harvest!  Thankfully, the Angustifolia and Intermedia lavenders bloom about 3 weeks apart, so this gives me time to first harvest the Angustifolias and then by the time I'm done with those rows, the intermedia are ready to go. Even better, within these two groups, there are varietal differences in bloom time. I am often asked how I know when it’s time to harvest. A good rule of thumb is to wait for the bees to arrive, but it also depends on what the harvest will be used for. If I am harvesting for culinary or for dried bouquets, I harvest when just a few flowers have bloomed. If I'm harvesting for fresh bouquets, then I harvest when about half of the flowers have bloomed. And if I'm harvesting for oil or for buds, I can harvest any time after that. For the Angustifolias, my French Fields is the first to bloom, which is always very exciting!! I harvest this one for culinary buds and just a few fresh bouquets, since the color is a lighter shade of purple and not as striking as the Royal Velvet for dried bouquets. Very close behind the French Fields is the Felice lavender, a semi-dwarf variety that I use to make the most beautiful wreaths. Its color is a deep navy, the buds stay put, and it keeps its color even when dried, so it’s perfect for wreaths. And finally my favorite Angustifolia -- Royal Velvet. Why is it my favorite? It’s good for just about every purpose and it is just gorgeous! It’s a wonderful culinary, stunning fresh bouquet, lovely dried bouquet, and smells divine. I made the mistake one year of putting off my harvest of Royal Velvet because it was just so beautiful in the field and we were holding yoga classes in that field. So by the time I harvested, I could only use it for sachet buds. I actually ran out of dried bunches that year, so I learned that I needed to be more disciplined in my harvesting. I might be crying as I harvest that beautiful field, but at least I’ll have enough dried bouquets! Around mid July the intermedias show up to the party. I harvest the Impress Purple and the Gros Bleu around the same time for fresh and dried bunches since they bloom about the same time. These plants are about twice the size of the Angustifolias so it takes me a little longer to finish each plant. As a result, by the time I get to the end of the intermedia harvest, I am harvesting for oil and for sachet buds. Thankfully, the Gros Bleu makes a nice oil and the Impress Purple makes good sachet buds since they are past the window for fresh or dried bouquets. Grosso is the last Intermedia I harvest because it will be used just for oil which I will use in my products, along with the oil from the Gros Bleu. I found that I had to increase my plantings of grosso since I was running out of oil a few months too early and had to depend on the Gros Bleu oil. Not a bad substitution, but the Grosso essential oil is just so divine!  Harvesting is easy, though a bit hard on the back. To harvest, I grab a handful in one hand and with my other hand, I use my hand sickle to cut down as low as I can without hitting the woody part of the plant. This gives me nice long stems (especially important for the dried and fresh bouquets), but also serves to (somewhat) prune the plant and leaves it looking tidy without any unsightly empty stems sticking up. Once I have cut my bouquet, I secure it with a rubber band and continue down the row. Once the row is done, I gather up my bouquets and head to the barn where I have a drying room just for lavender bunches. I have chains hanging from the ceiling about 3 feet apart, and from these chains I hang the lavender using a paperclip. All very low tech and a slow process, but it works, and I get to hang out with the bees and inhale the sweet smell of the lavender whenever a little breeze comes by. From the end of June to mid August, this is what I do every morning until it gets too hot. Not a bad way to spend a summer morning I’d say! I'll be honest. Until about four years ago, I didn't like goats.

Maybe it started in my younger Catholic school days with that Biblical passage about the shepherd separating the “good” sheep from the “wicked” goats Or maybe it was their weird eyes. Whatever the reason, I just didn’t like them. I always dreamed that once I had my farm, I would raise a few sheep, sheer them, spin the wool, and make a blanket or two. So raising goats never even crossed my mind. But our new farm came with a couple of goats, which we renamed Laverne and Shirley, so I was going to have to be OK with them. Laverne was a brown and white Boer/Toggenburg mix and Shirley was a brown and white Boer with floppy ears. I was a little nervous the first time I walked into the barn to meet them, what with all of my goat preconceptions floating around in my head. I thought they would be standoffish and creepy and maybe even mean. But instead they were curious and friendly...and funny. Especially Laverne, who boldly walked up and looked me straight in the eye, with her big beautiful weird eyes, as if she were trying to figure out if we would be friends or not. After a few minutes, she got so excited that she literally bounced off of the walls of her stall a few times. So I took that as a “yes, we will be friends.” Shirley, on the other hand, stood quietly behind Laverne and nervously looked at us, not sure what to make of these new humans who had suddenly appeared. After just a few minutes with those two, I was more than OK with them -- I was smitten! And I was ready to embrace my new role as goat owner. Our first goal as goat-owners was to get Laverne and Shirley out into the field to enjoy the sunshine, eat some fresh grass, and do a little clean-up (goats like to eat blackberry bushes, which we have an abundance of). So after getting some pointers from my brother John and doing a little research online, I put together my shopping list and headed off to the local feed store to get my goat supplies. A box of goat treats, two red collars, and a long lead later, and I was ready. That afternoon, we put the red collars on them, leashed them up, and took them for their first “walk” out into the field. But a few minutes in, Shirley got spooked and bolted, almost choking herself, so we nervously took the leads off, thinking it would be safer without them. We were ready to tackle one or both of the goats should they make a break for it -- but they didn’t. Instead they followed us wherever we went, nibbling on dandelions and blackberry bushes and wagging their little tails along the way. If we walked over to the trees, they followed us. If we walked to the road, they followed us. And sweet little Shirley, and her cute floppy ears, was bouncing around with pure happiness. At that point, I was too. So I got two more. Little Alpine babies this time named Opal and Emmylou. We got to bottle feed them for a short time, so I became “mama” to them and they became my babies. Watching their little tails wag at warp speed when they were sucking down that bottle of milk was one of the most wonderful things I’d ever seen. Even now that they’re older, they greet me with nose nuzzles and wagging tails and if I dare to sit down, they try to sit in my lap. Now I was told that goats don’t like to eat lavender, but Emmylou and Opal anyway have proven that to be a lie. They like the taste of lavender very much. I tried to tempt them with Douglas Fir branches or dandelions, but they kept going back to the lavender. So we built a nice big “goat run” right off of the barn so that our poor little plants had a chance. In the winter though, when the lavender isn’t blooming, I let them out to run around in the big field and let them take a few nibbles. There is still so much to learn about these wonderful creatures, but I’m looking forward to the challenge. Because goats are awesome! How can anyone not love them?!  One of the little joys of living on this farm (besides growing lavender of course!) is going out to the chicken coop in the morning to retrieve our breakfast. The happy clucking of our chickens as they scratch around their fenced enclosure, or the proud announcement that they have just laid an egg help to make our farm the wonderful place it is. Not only that, (and this might surprise you) but those chickens have quite distinct personalities. For example, the youngest chickens I have right now remind me of a bunch of rebellious teenage girls -- they all stick together, they’re always pushing boundaries (they lay their eggs all over the barn!), and they love to annoy their goat siblings. One of them even keeps trying to lay her eggs in the goat’s hay feeder, which the goats are not happy about at all! Over my years as a “chicken mama,” one chicken in particular, a little Rhode Island Red named Lucy, was particularly memorable -- because this chicken thought she was a dog. Early on, I knew she was different. Though she had a nice large garden area to wander around in, that wasn’t enough for her, and she would fly up on top of the garden fence, hop over, and wander around the rest of the property. Now one of the reasons I had put that chicken fence up was because we had a dog named Jake who didn’t understand that the chickens were not his dinner. I can’t fault him of course -- his natural instincts were just kicking in. But he had already killed a few of our chickens and although he had been scolded, I knew that he would kill more if given the opportunity. So up went the fence. Lucy didn’t understand that of course. She was a very friendly chicken and just wanted to be with everyone else, especially me. In fact whenever I came outside, she would run up to me and squat down so that I could pet her. So to try to keep her safe, whenever I saw her out, I would go outside and pick her up, tell her in no uncertain terms that the fence was for her own protection and put her back in her enclosure -- also talking to Jake to try to communicate that this chicken was off limits. This went on for a while -- I’d see Lucy outside of the fence, go outside and pick her up and put her back in the garden enclosure. And Jake would look up at me, distressed, confused, and fighting so hard with his natural instincts, trying to leave that chicken alone. And then one day when I went outside, Lucy came out from under the deck (which was Jake’s special place), and at that point I knew we were in trouble, because Jake definitely did not appreciate the intrusion into his special spot, especially by a chicken that he wasn’t supposed to eat. So I picked her up and put her back and knew her days were numbered. As you might guess, one day it was just too much for him, and we lost that funny little hen. But I never faulted Jakey. And I never forgot that hen. This is something I’ve had to get used to -- losing animals. I don’t like that part. But I cherish every little life that has been entrusted to me, love their unique personalities, and am grateful for their gifts and the joy they bring to us all. Spring is all about weeding and light pruning and planting (and replanting) and fixing. And waiting. Lots of waiting. First the weeds. Even with a weed barrier, there is weeding to do. So we start with a good mowing, a thorough weed-whacking, and then the hands and knees fun of pulling weeds out of all the nooks and crannies that weeds get themselves into, often growing up through the lavender plant itself. While I’m down there, I will work in a little compost and lime around my plants, only because our soil has a lot of clay in it. This is also the time where I will do some light pruning to remove any dead parts of the plant or reshape. Pruning also stimulated the plant to start growing, so that's an added bonus! As I'm weeding and pruning, I will also identify plants that didn’t survive the winter. Thankfully, because we live in a mild climate and because lavender is so hardy, it’s usually not too many. How can I tell? Quite honestly, sometimes it’s kinda tough because lavender in its dormant stage looks pretty dead. But if I see a plant that doesn’t have any new growth on it, or if a plant only has new growth on a small part of it, then I will yank it out and replace it with a new plant. I think the first year I did this I was a little over zealous and pulled out plants that might have survived with a little pruning and patience. But these are the lessons you learn along the way. Spring is also the time where I plant new rows of lavender. Every year I tell myself that I have enough lavender and that I don’t need anymore. But then I hear about a new variety or decide I want to change up the color a little or I’m not happy with the performance of a particular lavender variety (I’m looking at you Impress Purple) and I will add to or replace a row. Yes, this year I will cut back on the Impress Purple and replace it with more Grosso. And I’m adding just a few rows of Riverina Thomas. Oh, and just one row of Arctic Snow -- a white lavender!

Finally, once this is all done, I check the irrigation (which we only use occasionally) and replace the 10 million emitters that need to be replaced because they’re either clogged or got whacked by the weed whacker. And there are probably a few hoses that got mangled by the lawn mower. And some of the weed cloth probably needs to be stapled down a little better. And the field signs probably need some touch up. During this time, the lavender has been reawakening. We see the leaves start to green up in April and May and then the little lavender heads start to peek out from the greenery, eager to take center stage. As they continue to reach skyward, their stems and heads are floppy and flimsy, but toward the middle of June they start to get stronger so that by the end of June the Angustifolias are ready to be harvested, with the intermedias a few weeks behind. I appreciate this and applaud my wisdom in having a few different varieties that bloom at different times to help me out. Because if I had 900 lavender plants all blooming at the same time, well, I might not be so enthusiastic about lavender farming. So Spring is a busy time indeed...but soon it will be even busier! |

Categories

All

Archives

May 2022

AuthorHello! My name is Pam Reynolds Baker and I am a mom/wife, writer, and lavender farmer who lives in Dundee Oregon . |

- Home

-

Lavender 101

- Our Lavender

- A Brief History of Lavender

- The Many Uses of Lavender Essential Oil

- Choosing the Best Essential Oil for You

- What is Hydrosol anyway?

- Lavender and Anxiety

- Lavender and Weddings

- A Lavender Home

- Lavender and Soil Amendment

- Growing Lavender in Containers

- When to harvest lavender

- Cleaning Lavender Buds

- Pruning

- Shop

- Recipes

- Writing

- Lavender Crafts

- Gallery

- About Us

- Press

- Privacy Policy

RSS Feed

RSS Feed